The Big Mac Index: Purchasing Power Parity

In light of the Christmas season upon us (or just past us – depending on when you’re reading this), and the approaching New Years Eve celebrations, I thought it be appropriate to write about something a little more lightweight. And that is: purchasing power parity (PPP). A conversation about this came to mind while I was hosting Bruski’s 3rd Annual Christmas Soiree this December for my colleagues. One of the conversations at our table, after a seemingly gluttonous meal, was how we could all still go for some McDonalds at the drive-thru. This soon turned to talking about the economics of their business, the value of their real estate (which is unlikely to come to fruition in the near future), and the degree of inferiority, as compared to normality, of their product during recessionary times. Great dinner conversations right? The conversation digressed into other economic, political, and business related subjects, but eventually came ‘round full circle to McDonald’s with the subject of PPP.

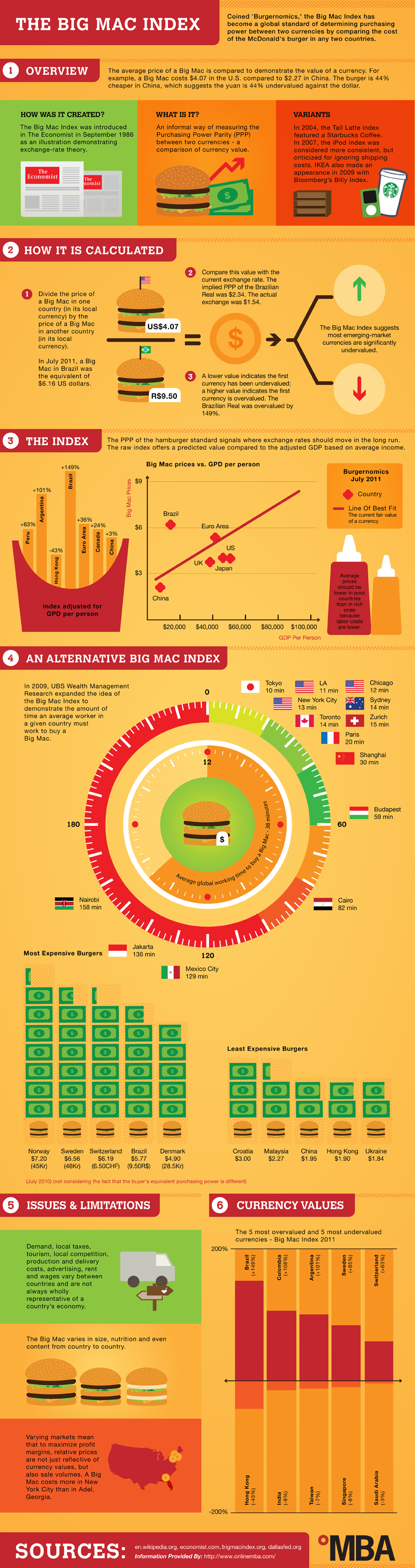

PPP is a fundamental theory in economics that basically estimates the adjustment that is needed to be made in the exchange rate between two countries in order for the countries to have equal purchasing power of their currency; meaning they can buy the same amount of products for the same amount of money. It’s calculated by dividing the cost of the same product in one currency by it’s cost in another currency, which should be equal to the exchange rate. For example, if a bag of chips costs $1.50 in Canada, it should cost $1 in the US if the exchange rate is 1.50 USD/CDN. If this doesn’t end up being the case… well, then there are a whole lot of other things to discuss. (There is also something called interest rate party IRP that has the same premise but states that the interest rate differential between two countries is equal to the differential between the forward exchange rate and the spot exchange rate – we can talk about this a different time as there is also covered and uncovered interest rate parity to think about).

What I’ve described above is called Absolute PPP and is based on The Law of One Price – an idea that states that the Real price of a good must be the same across all countries. In order for this to hold true, a few things must be present:

- The goods in each country must be freely tradable internationally

- The price index (a weighted average of prices for a given basket of goods) for each of the two countries must be made up of the same basket of goods

- All of the prices need to be indexed to the same year

Obtaining conditions like the ones above starts to get quite difficult in a world that is so fast paced and diverse as the one we live in. Therefore, some economists use relative PPP. With the same intentions, relative PPP relates the change in two county’s expected inflation rates to the change in their exchange rates – because inflation reduces the purchasing power of a dollar. Not that it matters much to this post, but relative PPP is calculated by dividing the expected and annualized inflation rate in a foreign country by that same number for the domestic country. The result should be equal to the one year delta (change over one year) in the spot rate as measured by the value of the unit of the foreign currency per unit of domestic currency. Blah – sounds like a verbal smorgasbord of who knows what.

In 1986 a very famous magazine, you may have heard of, called The Economist published a lighthearted article about the McDonalds Big Mac and how, because of its rapid and widespread international success, it can be used as a benchmark to gauge PPP and whether currencies are at their “correct” levels – because according to PPP, in the long run, exchanges rates should adjust so that the Big Mac costs the same across borders. The initial concept of “burgernomics” wasn’t meant to be a scientific process but instead an analogy to make the theory more “digestible”. However, its taken on a mind of its own as it’s used as an international standard, published in textbooks, and the subject of numerous academic studies. The Economist even provides an online calculator that allows you to compare countries. As of July 2015, with the US dollar as a benchmark, only Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Switzerland are overvalued, while the four most undervalued countries are Russia, India, Ukraine, and Venezuela. Interesting Huh?

In either case, this leads to quite the Christmas Soiree conversation, and I’ve got to say, I was, indeed, “Lovin’ It”.